The Real-Life People Who Inspired the movie's real life characther

When The Brutalist movie premiered, many assumed its Hungarian protagonist, László Tóth, was based on one historical figure. In reality, the film draws from multiple Hungarian visionary artists who revolutionized modernist and brutalist architecture. Icons like Marcel Breuer, Ernő Goldfinger, and László Moholy-Nagy shaped the design world with their groundbreaking structures and furnitures. In this post, we’ll explore their lives, work, and lasting influence on 20th-century aesthetics.

Marcel Breuer (1902–1981)

Marcel Lajos Breuer was born in Pécs, Hungary, into a middle-class family. After completing high school in Pécs, Breuer received a scholarship to study painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. However, he quickly became disillusioned with the academy’s rigid atmosphere and left shortly after enrolling. Instead, he sought hands-on experience, working under a Viennese architect and learning cabinet-making in the architect’s brother’s workshop. Later, he would describe his time in Vienna as one of the unhappiest periods of his life.

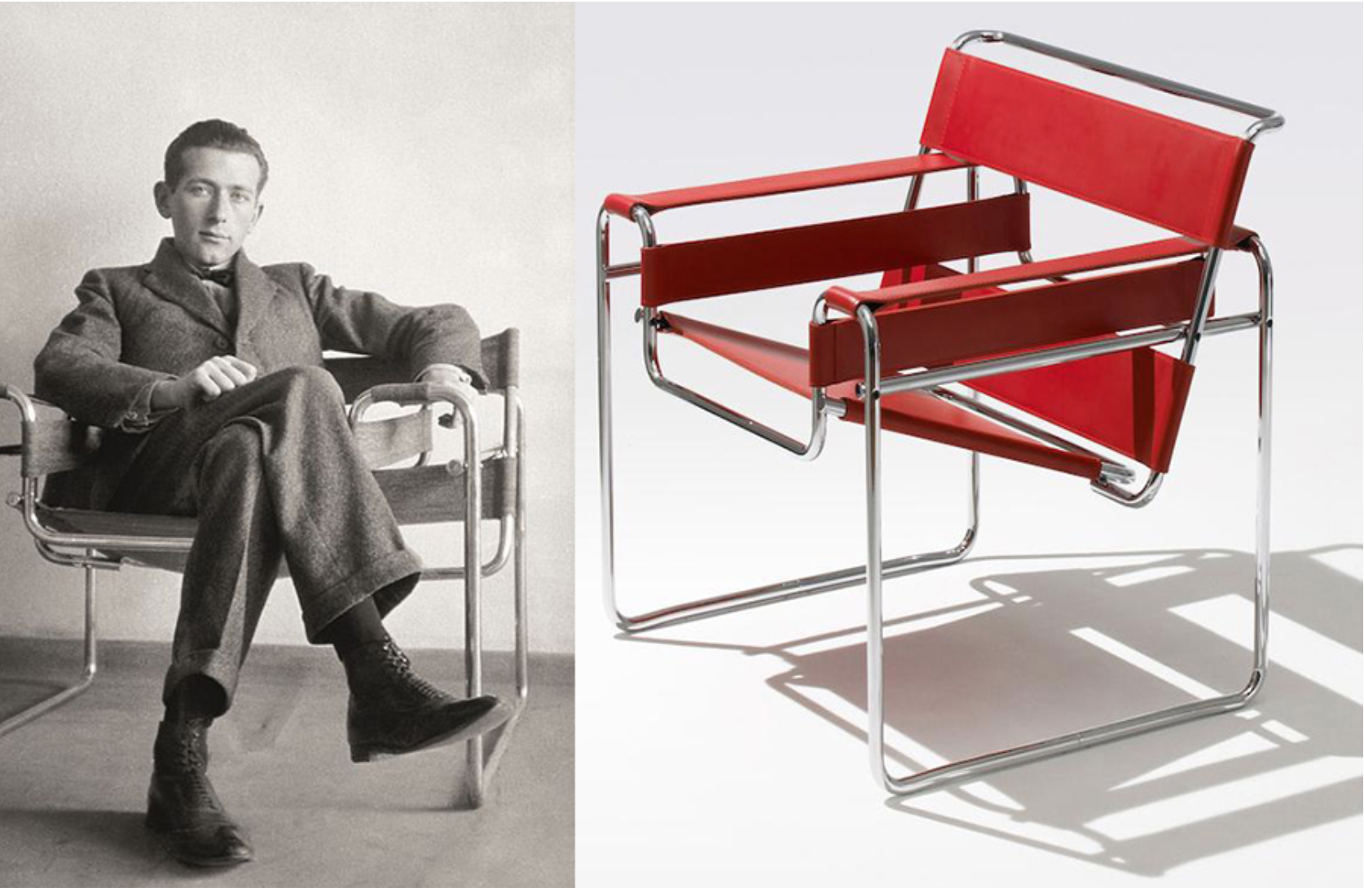

His career took a turn when he joined the Bauhaus in Weimar at the age of 19, becoming one of the school’s first and youngest students. Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius soon recognized his talent and promoted him to lead the carpentry workshop.

One of his most famous creations, the Wassily Chair (Model B3), was designed in 1926 at the Bauhaus. Inspired by the curved handlebars of his bicycle, Breuer experimented with tubular steel to create a chair that was lightweight, strong, and radically modern. By reducing the armchair to its most essential structure, he introduced a groundbreaking approach to furniture design that remains influential today.

The Cesca Chair (affectionally named after Marcel’s adopted daughter Francesca – nicknamed Cheska) was unveiled by Marcel in 1928. Famed for its striking cantilever design and bleeding-edge modernist aesthetics, the Cesca was the first tubular-steel frame chair with a cane seat to be mass-produced. Just like the Wassily Chair, an original example takes pride of place in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Beyond furniture, Breuer became a key figure in modernist and Brutalist architecture, known for his bold use of concrete and geometric forms. His architectural works, including the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, helped define 20th-century design. Through both furniture and architecture, Breuer’s legacy continues to shape the way we think about modern design—where simplicity, functionality, and innovation come together seamlessly.

László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946)

László Moholy-Nagy was born on July 20, 1895, in Hungary, to a Jewish-Hungarian family and was named László Weisz. He received his early education from an academic high school based in Szeged. At the advent of World War I, he went on to study law in Budapest. Soon after, he suffered a severe injury while serving in the war. In 1918, upon his discharge from the army, he enrolled himself at a private art school ran by the Hungarian Fauve artist Róbert Berény. As the Communist Regime was defeated, he moved to Vienna and then to Berlin.

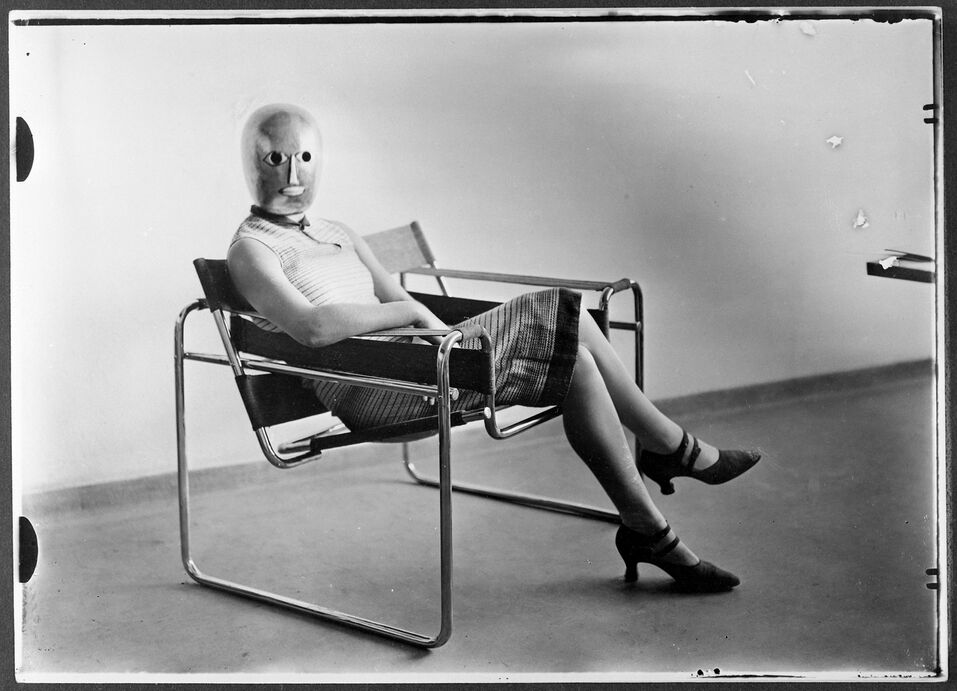

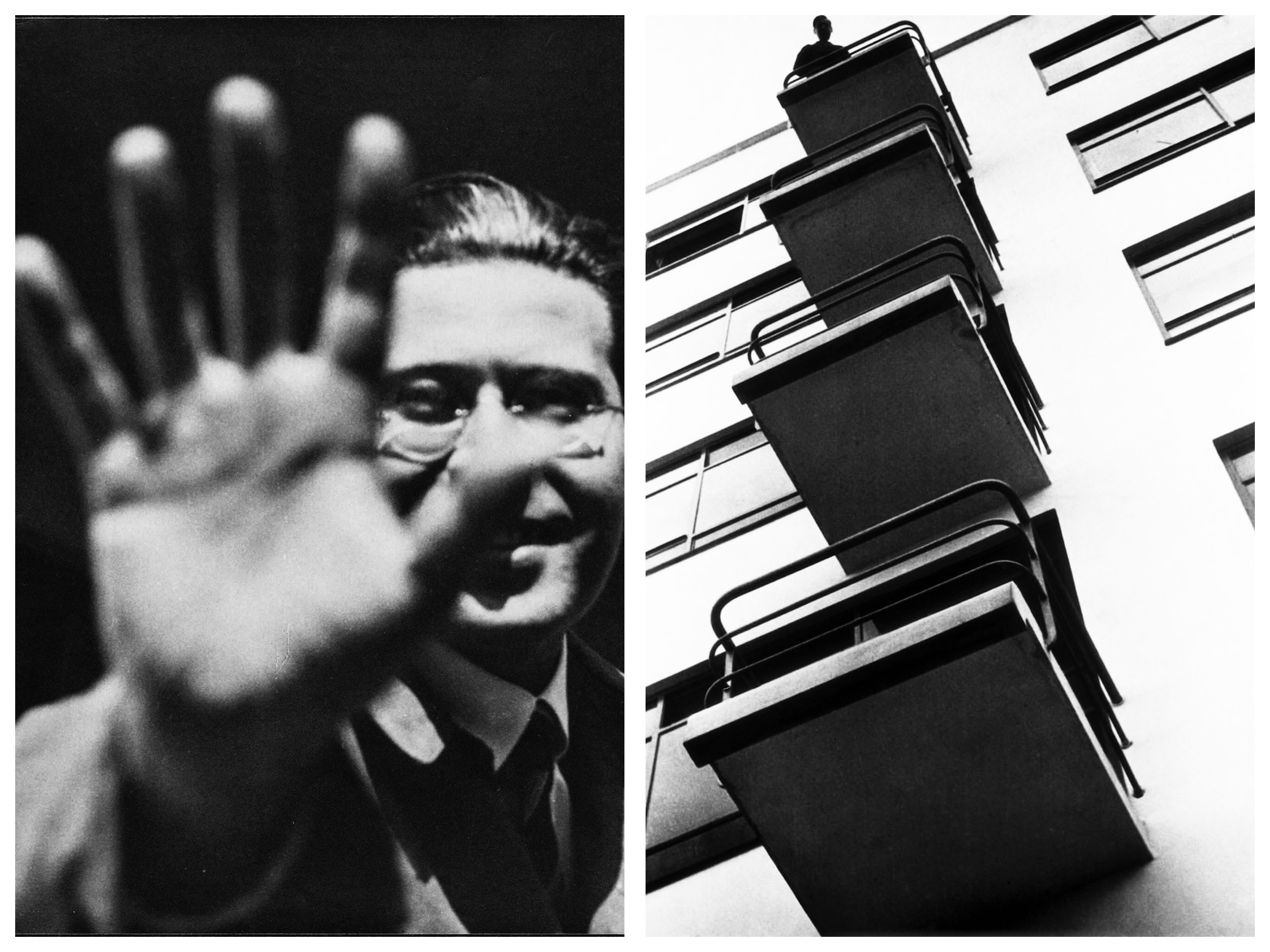

Moholy-Nagy took up the position as an instructor of the foundation course at the Bauhaus school, in 1923. He was recognized for his life-long effort and proficiency in a variety of fields including photography, typography, painting, sculpture and printmaking. However, photography remained his forte. According to his belief known as “the New Vision”, photography is the means of capturing reality in a whole new spectrum that is not entirely possible for human eye. His teaching had a profound influence on his students who seeked to explore the endless wonder of art in its various forms.

Moholy-Nagy moved to England as Nazis came to power in Germany and worked a number of jobs from teaching to commercial photography. He was invited to the US to hold the position of director of New Bahaus and remained in Chicago till the end of his days. In 1946, László Moholy-Nagy died of leukemia.

What was remarkable about Moholy-Nagy that he was almost entirely untrained in many other fields that he explored in his career. According to some of his friends, this lack of any conventional art education was what allowed him to roam freely across different fields and to remain innovative in everything he touched.

Ernő Goldfinger was a gruff and difficult person who, notably, built his modernist villa near the residence of James Bond’s creator, Ian Fleming, which led to the writer’s personal dislike of him. After the release of the spy novel, Goldfinger immediately sued Fleming, demanding the name of the villain, Auric Goldfinger, be changed. The matter was settled after an agreement involving compensation and six books, which also gave Goldfinger wider public recognition.

Born in 1902 in Budapest to a wealthy Jewish family, Goldfinger moved to Vienna in 1918 and never returned to Hungary. He completed his schooling in Austria and Switzerland and then went to Paris in 1920 to study languages. What was supposed to be a two-week trip became a 14-year stay. His passion for the arts led him to enroll in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he initially studied architecture, though he found the official curriculum uninspiring. Instead, he attended lectures by the pioneering architect Auguste Perret, which sparked his interest in modern concrete architecture. It was in Paris that Goldfinger became part of the vibrant artistic community, making friends with figures like André Kertész, Paul Éluard, and Max Ernst, and met Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus, whom he later considered his mentor.

Goldfinger’s personal life also took root in Paris, where he met his future wife, Ursula Blackwell, heir to the Crosse & Blackwell food company. They married in 1934 and moved to England, where Goldfinger was driven to design the country’s first modernist building. Despite creating the Willow Road villa in Hampstead, England's attachment to traditional architecture meant his work was met with resistance. The villa, with its large glass surfaces and simple lines, became the first modernist house in the UK and is now a museum dedicated to Goldfinger’s legacy.

Before World War II, Goldfinger focused on theoretical issues in architecture but quickly offered his assistance to authorities when Britain was attacked. He participated in camouflage efforts during air raids and was involved in post-bombing reconstruction. During this period, he wrote The County of London Plan, a city planning bestseller.

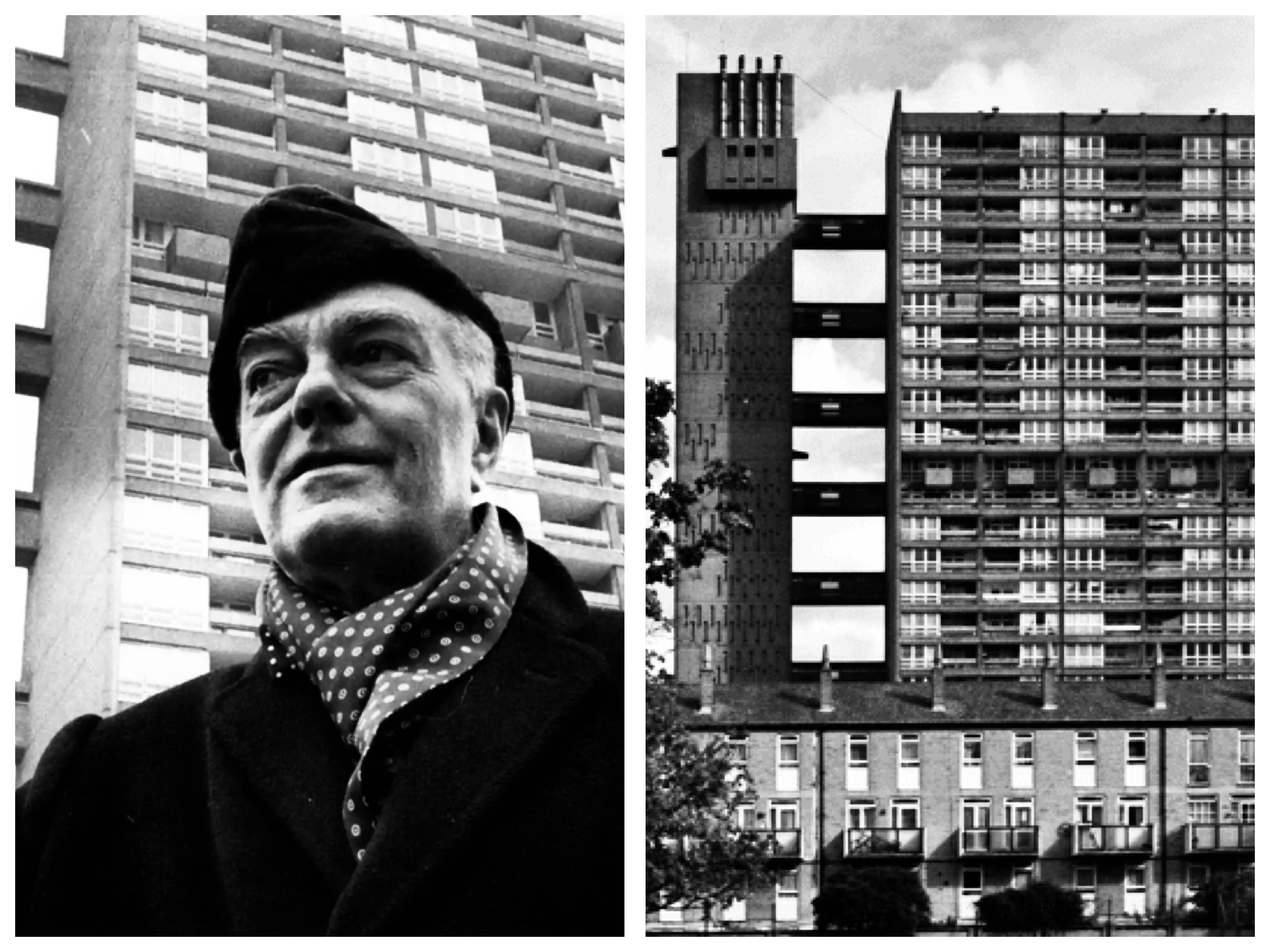

After the war, Goldfinger's architecture firm flourished, and he designed schools, residential, and public buildings. He became one of the leading figures of the brutalist architectural style in Britain, developing a modular system for rapid construction using prefabricated concrete elements. His design innovations included the photobolic window, which used a horizontal divider above eye level to project light onto the ceiling, making rooms appear brighter. Despite his notoriously gruff and humorless nature, his drive and perfectionism attracted many young architects to his office.

Among his most notable works are the building constructed for the British Ministry of Health, now known as the Alexander Fleming House, and the Odeon Cinema, both completed in 1967. Also in the same year, he completed the 26-story Balfron Tower, where Goldfinger himself moved in with his wife on the top floor to directly assess the livability of the building and gather feedback from the residents.

After initial misunderstandings, his work was eventually recognized with awards. In 1971, he was elected a full member of the Royal Academy of Arts, although he declined the title of knight. He ceased designing in 1977. Goldfinger remained proud of his Hungarian roots throughout his life, and his accent never changed over the years. He arranged professional internship opportunities in London for architecture students from Hungary. Later, he established a scholarship for talented young architects, with the stipulation that there should always be a Hungarian recipient among the awardees.

In the final years of his life, he visited Hungary several times and gave lectures at the Technical University. He passed away in London in 1987.

If you liked this article you can follow us on Instagram or Facebook.

Are you moving to Budapest?

Call or text today, we are here to help!

Phone: +36 30 166 12 34

EMAIL: info@mhomes.hu

sources:

https://kultura.hu/goldfinger-erno-epitesz/

https://www.famousgraphicdesigners.org/laszlo-moholy-nagy

https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/know-your-architects/a3532-10-things-you-did-not-know-about-marcel-breuer/

https://wheresaintsgo.co.uk/blog/designer-details-a-brief-history-of-marcel-breuer.html

https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/london/2-willow-road